Grade inflation and its effects at FISD

Inflation. While this term has been trending lately following the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been active in academic fields for over half a century.

But what does this term mean and how did it come into place?

Just like economic inflation, grade inflation refers to the rise in the average grade of students across the country. This practice started during the 1950s where professors gave out higher grades so students wouldn’t be drafted to fight in the Vietnam war, and has been in practice ever since. For instance, the average GPA in four-year universities rose by about 0.4 from 1983 to 2014, and this number is lower when compared to the change in GPA from the 1950s to right now.

While grade inflation may seem beneficial as it’s helping students pass classes easier, it comes with a trade off: it gives students the false hope of mastering a subject when they’re far from it. However, while GPA has risen over the years, SAT scores have done the opposite, indicating a grade/GPA inflation.

To put grades and grade inflation into perspective, let’s look at the FISD grading policies.

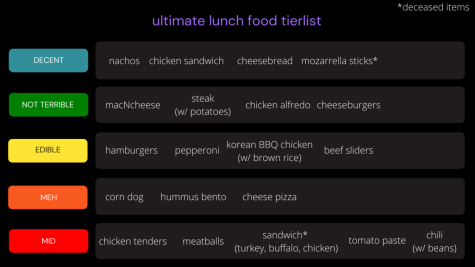

FISD, and as an extension LTHS, uses fractional grading, a system where each grade has a different GPA value i.e., a 100 on an on-level class results in a 5.0, a 99 results in a 4.9, and so on (for more information on grading policies, refer to pages 16 to 21 on the 2021-22 FISD High School Academic Guide and Course Catalog). In addition, students have the opportunity to showcase learning and mastery through two policies: waterfalling and retesting.

If a student scores a higher grade on a test, PG (progress grade) quizzes that lead up to the test “waterfall,” i.e., their scores will be increased to the test grade. In addition, if a student scores less than a 85 on a test, they may retest up to a 85.

Starting this semester, however, some FISD schools updated their reassessment policy to allow students to retest up to a 100. While LTHS has not implemented this policy yet, should it be put into practice, I believe it will do more harm than good not just to students, but to teachers as well.

Students are given two opportunities, namely waterfalling grades and reassessments, to showcase growth in a topic and improve their grades. Most teachers don’t heavily penalize late work either. While I’m grateful for these policies as many students participate in extracurricular activities and might have a hard time keeping up with homework, having more than two chances to improve their grade would make them lazy and diminishes the importance of quizzes and tests.

A contrasting effect, though, would be students becoming perfectionists. In a competitive school like LTHS, the update to the reassessment policy would result in students retesting a 90 or even a 99 just so they could get a 100 and be in the top 10% of their graduating class (especially due to the Texas House Bill 588 and fractional grading where every single point matters). But let me clarify that I do not condemn students for playing by the rules and trying to maximize their grades as much as possible in order to have better chances of getting into competitive universities; I blame the system for encouraging and fostering an environment where students can overstress themselves over grades and class rank.

With an increase in the number of students wanting to reassess as a result of the update to the policy, teachers— who are overworked and underpaid already— would have more tests to make and work to do. While it is a teacher’s job to administer tests and give grades, a sudden increase in reassessments would only make their lives harder.

Moreover, students’ views on what constitutes a “good grade” would shift as a result of the update. If a student does poorly on a test, they can review their test, study harder, and potentially get a 100 on the reassessment, waterfalling all PG quiz grades. While this may sound helpful to students as it encourages them to demonstrate mastery of the material better than with the 85% cap, I’m afraid students (especially those in challenging classes) will regard any grade less than a 90 or maybe even 95 unacceptable.

Many students base their self worth off of the grades they receive, and if they don’t receive a 100 after the retest, their self esteem will plummet; they might even feel belittled for not being able to achieve an “acceptable” grade despite the reassessment cap being removed (along with other grading policies in LTHS). According to a 2002 study conducted by a professor from the University of Michigan, more than 80% of the surveyed students (college freshmen) stated they base their self worth on academic achievements. This number is more of less similar to what one might find in competitive high schools like LTHS. With such a high number, I’m afraid students will be more likely to rely on unhealthy coping mechanisms to deal with the increase in pressure to obtain desirable grades.

In addition, high school is supposed to prepare students in navigating through college and life. While not all students want to pursue a two or four year college, for those that do, a policy like this does not prepare students well enough to manage the rigor of college coursework, widening the gap between high school and college. I do not think high school should be as hard as college— it’s a stepping stone after all, but I don’t think it should be as lenient as it will be should the reassessment cap be removed in LTHS.

While students interested in pursuing an undergraduate degree may be concerned about being compared to other high school students throughout the nation and world during the college admissions process, they need to keep in mind that colleges take into consideration the students’ circumstances and their school’s curriculum and offerings. In this case, the reassessment policy works against the students as college admissions officers for selective universities have a higher expectation for students from LTHS as they were given a second chance to completely make up for their test grades all the way until a 100 along with being able to waterfall their quiz grades.

For example, when I changed schools last year, I was very concerned about how different courses and policies at LTHS and my previous high school (Milpitas High School) were as it negatively impacted me. While there were many differences between the two schools, the one that affected me the most was MHS’ AP cap i.e., at MHS a student may not take more than three AP courses a given year; plus, freshmen could not take an AP or Honors (pre-AP) course whatsoever. Here in LTHS, there is no cap on how many AP courses a student wishes to take and students are offered way more courses, which negatively impacted me. However, I spoke to Trinity University’s admissions officer for the Dallas area who reassured me that my circumstances and the differences between both schools will be taken into consideration given that I mention them in my application.

Similarly, if a student feels the need to include additional information not in their essay or anywhere else on the application, the Common Application and many other portals have an Additional Information text box where students can write about anything they wish to be considered when their application is being reviewed. Therefore, students need not worry about course offerings and the grading policies at another school.

Overall, the update to the reassessment policy helps students that are sick during the test and gives students a second chance at showing mastery of the topic. However, it comes at the expense of students’ mental health and teachers’ workload.

Should LTHS update the policy like other FISD schools, I suggest that school officials equip students with better mental health resources by raising awareness and a school therapist the students can confide in when they feel stressed or overwhelmed.

Like with the rest of the nation, inflation is prevalent in FISD and while I’m grateful for the current grading policies, I believe updating the reassessment policy will hinder students’ growth.

The only senior in Vanguard News, Vaishnavi Josyula strives to voice Class of 2022 and hopes to continue Newspaper in college. She enjoys Math (especially...